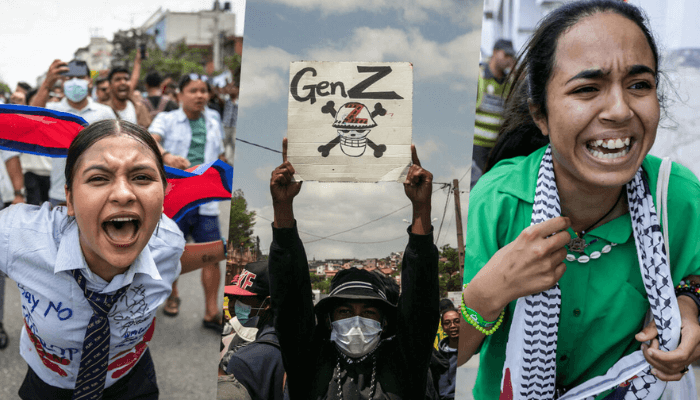

When I first saw photos of young protesters in town squares in Nepal, Madagascar and Morocco with slogans boldly written on placards, like “There is corruption, end democracy”, I half smiled, thinking: This slogan could have come up in a group chat of any Lagos teenager. This is not a mere coincidence. The phenomenon of youth-led protest movements around the world, often driven by the generation of 'Gen Z' (born approximately in the late 1990s to early 2000s), has implications that are powerfully localized in Nigeria.

In disparate places like Indonesia, the Philippines, Kenya, and Peru, youth connected through shared social media platforms and frustrations with governance have emerged as powerful forces. In Nepal, a sudden ban on social media triggered mass mobilization; In Madagascar, a rebellion broke out due to breakdowns in water and electricity services. Although the immediate catalysts are different, the underlying story is familiar: young societies, frustrated by systemic failures, use digital networks to call for collective action.

“Nigeria must therefore be wary of trigger events: a major fuel-price shock, Internet shutdown, sudden increase in food inflation, election manipulation, persistent insecurity, police harassment and unabated suffering. Anyone can provoke mobilization.”

It's easy to think of the wave of uprisings during the Arab Spring in the early 2010s when youth in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and beyond overthrew established regimes. Many of those hopes were dashed without meaningful improvement in young lives. Today, the Gen Z wave seems to be a sequel, faster, more global and more digitally native, and Nigeria may be on its way.

In Nepal and Madagascar, lower average ages (28 and 21, respectively) helped create movements based on young populations, high unemployment, weak governance, and ubiquitous social media. The same structural realities are visible in Nigeria. According to the latest survey by Afrobarometer, Nigeria's median age is about 18.1 years, and 58 percent of the population is under 30 years of age.

Young Nigerians are reporting intense negative impacts about their economy and personal prospects. A survey shows that only 6 percent of young people think their government is doing “fairly well” on jobs, and only 2 percent believe inflation has been handled competently.

And the unemployment story, even with the statistical caveats, is troubling. Official figures report 6.5 percent unemployment among 15-24-year-olds in the second quarter of 2024, but many analysts argue that the real level of youth alienation is much higher.

Digital culture has helped connect these young citizens into a global tribe. Across continents, platforms like TikTok, Discord, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc. have become common protest grounds. In Nepal, protesters cited movements in Indonesia; In Madagascar, even young journalists saw inspiration from Nepal. This chain connects Lagos to Kathmandu.

What happens when similar ingredients come together in Nigeria? A large youth population, rising cost of living, underemployment and a feeling of being left behind. The setting is prime for unrest. In Nigeria, more than 80 million people live in poverty; Youth unemployment (or lack of meaningful employment) is often cited as a root of insecurity and unrest.

Gen Z in Nigeria is not just an audience. They are electronically connected, socially aware and politically disillusioned. According to Afrobarometer, 23 percent of youth aged 18-35 say they are unemployed and actively looking for work, while many others say they are unwilling to remain passive.

Can these young Nigerians replicate the rebellions seen elsewhere? It is possible. Many characteristics are similar: a young population, digital connectivity, a sense of exclusion or betrayal, and visible failures of infrastructure and governance. And as we've seen elsewhere, these protests can escalate surprisingly quickly.

Also read: Madagascar plunges into chaos due to Gen Z rebellion, President forced to go into hiding

Yet herein lies the fundamental paradox – Gen Z protesters can drive change, but they can't control what happens next. In Madagascar, after protests that ousted the president, a former opposition politician took over leadership of the legislature, sparking frustration among a youth-led movement that feared its energy had been co-opted. In Nepal, a youth activist said, “What if everything goes the same way, even though we have lost our blood and lost our comrades?”

The crux of the matter is that, even ensuring regime change does not guarantee structural change, especially when the issues are deep and systemic. As researcher Abigail Branford says, “Youth unemployment, weak institutions, patronage, and weak economies cannot be easily reversed by simply picking up the boards.”

In Nigeria, the stakes are high. Any protest may lead to demands, resignations or policy pledges, but unless deep economic, governance and institutional deficits are addressed, youth activists may find themselves disillusioned. The current administration's focus on youth empowerment and skills (for example, through vocational training) is welcome, but critics argue that it is inadequate given the sheer scale of the challenge.

Nigeria should therefore be wary of trigger events: a major fuel-price shock, Internet shutdowns, a sudden spike in food inflation, election manipulation, persistent insecurity, police harassment and unabated suffering. Anyone can instigate mobilization.

Digital mobilization: a flyer, a viral TikTok video from a northern city, and a WhatsApp chain calling for a “Walk for Jobs” in Lagos. Unexpected alliances: Young students, informal sector workers, and tech-savvy creatives unified by hashtags and common experience.

Post-protest risk: If the power vacuum is filled by old-guard elites without any meaningful reform agenda, the next generation may feel disillusioned, and the energy of the protests may dissipate or become destructive.

For Nigeria, this is not a distant scenario. The youth have shown that they are ready. The question is, will the political and economic systems respond in time? The old models of patronage politics, short-term programs and marginal business plans are inadequate. If young Nigerians feel that their values, their vocabulary and their demands for respect go unheard, they can write a new chapter.

Like the Arab Spring before it, the Gen Z uprising is both a promise and a warning: a promise because young people are no longer powerless and a warning because accommodating their voices requires structural change, not just rhetoric.

In the case of Nigeria, what may seem like another protest wave may develop into a turning point. The youth are connected. They are disappointed. They are watching, and they have the power. Contagious disease is not destiny, but ignoring it can be destiny.