Last Monday, October 27, I participated in the 2025 Fiscal Policy Conclave organized by the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) held at the UP College of Law. There were simultaneous panel sessions in the afternoon. I participated in the panel on “Digitalization and Process Innovation” with three speakers: Department of Finance (DOF) Undersecretary Renato Resid, Jr., Ateneo de Manila University Professor Albert Matthew Alejo, and Department of Economy, Planning and Development (DEPDev) Undersecretary Joseph Capuno.

In the second set of simultaneous discussions, I participated in the panel on “Fiscal Stability and Sustainability,” which also featured three speakers: Ateneo Professor Elvira de Lara-Tuprio, Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department (CPBRD) Director Ricardo Meira, and Bangko Sentral Director John Michael Hollig.

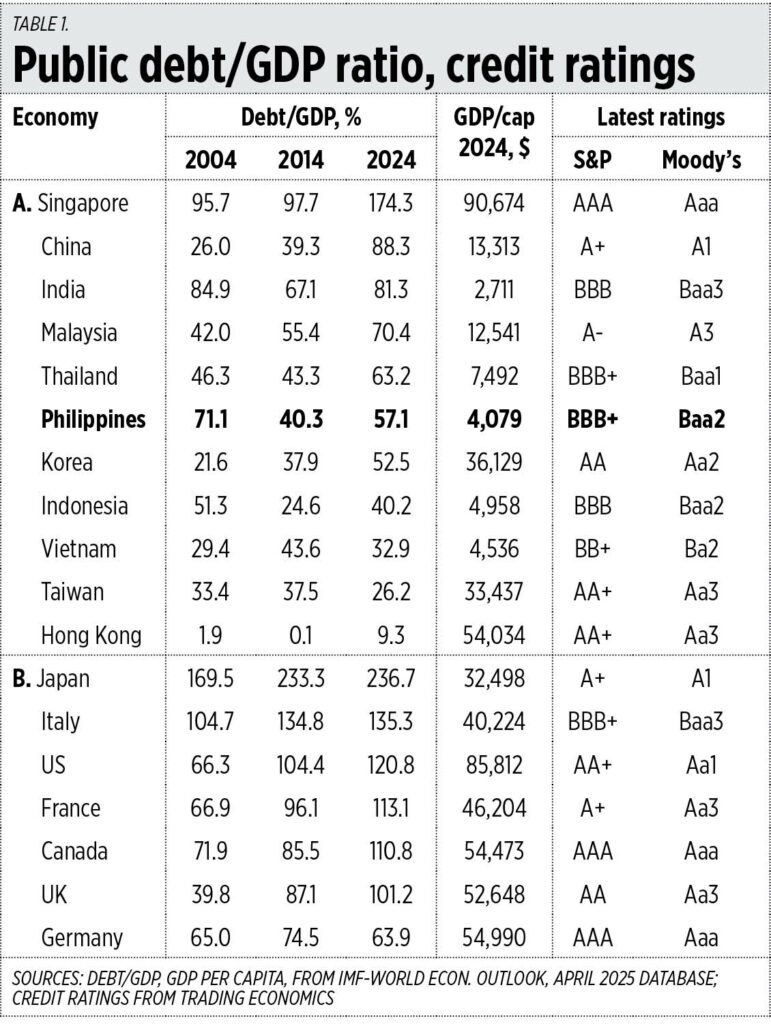

Among the topics discussed in the two sets of panels was why countries with high public debt/GDP ratios above 100% (such as Singapore, Japan, the US, France) have credit ratings ranging from A+ to AAA and, therefore, can borrow at lower interest rates, while countries with debt/GDP ratios below 90% (such as India, Thailand and the Philippines) have a lower credit rating of BBB.

One explanation given is that countries with a high rating have a per capita GDP income of $30,000 or more, while countries with a BBB rating have a per capita GDP income of less than $8,000. But there are exceptions here too. The economies with low debt/GDP ratios and per capita income and higher ratings are Taiwan and Hong Kong (See Table 1,

The Philippine economic team – DOF, DBM, DepEd Secretaries and Special Assistant to the President for Investment and Economic Affairs – continuously aspire and hope that we will reach a credit rating of A before the end of the Marcos Jr. administration. And this is right because despite the absence of any economic or virus-related crisis like the lockdown of 2020-2021, our annual borrowing is not declining.

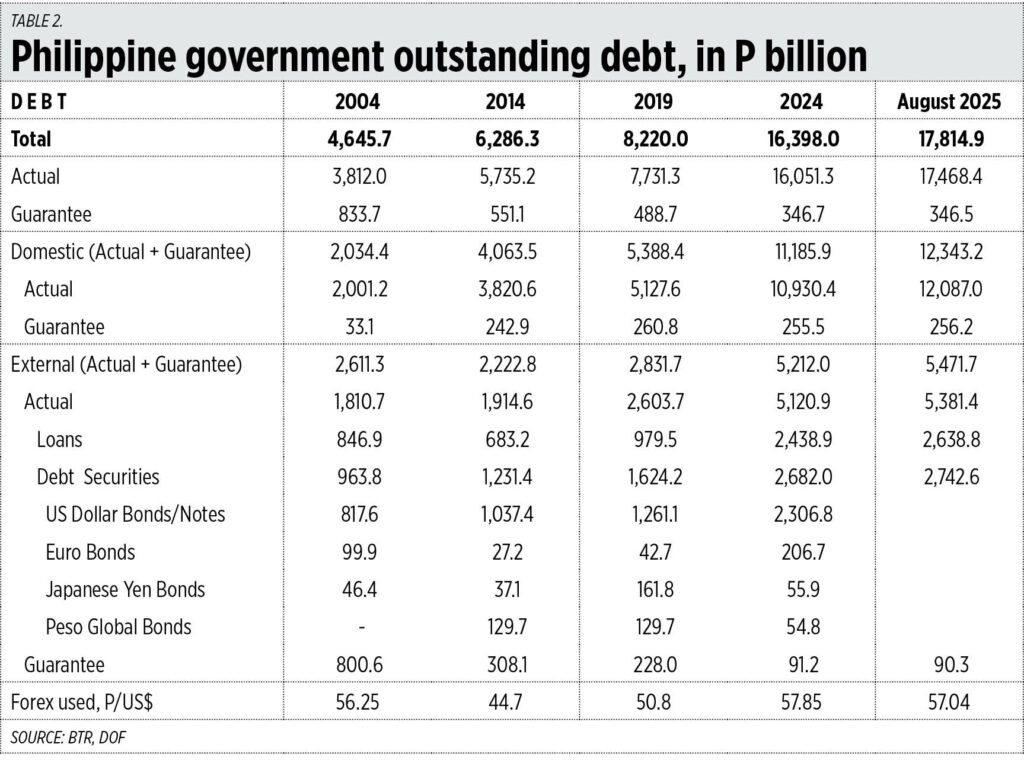

Before the lockdown, the Philippines' outstanding debt (actual plus guaranteed) stood at only P8.22 trillion in 2019. It then rose to P10.25 trillion in 2020, P12.15 trillion in 2021, P13.82 trillion in 2022, P14.97 trillion in 2023, P16.40 trillion in 2024, and P17.81 trillion in August. 2025. In other words, public debt was growing by an average of P1.64 trillion/year, which is equivalent to a budget deficit of about P1.55 trillion/year over the same period.

While guaranteed debt generally remains below P400 billion, it is the actual debt that continues to grow – P17.47 trillion as of last August (See Table 2,

One thing I noticed on Monday was that there were little or no proposals from speakers to make significant cuts in expenditure, to reduce the public debt, at least to balance with projected revenues.

Perhaps this is one reason why DBM invited me to participate in the forum to present this perspective. But I decided not to ask questions during the panel because there was very little time. I enjoyed listening to and understanding the concepts and methods that government academics and speakers presented, including their complex Greek mathematical and regression equations.

One thing I've noticed among agencies – if they see that new sources of revenue or borrowing are available next year, they immediately come up with new ways to spend and new subsidies or expand existing methods. The high debt/GDP ratio and high interest payments (averaging about P2.6 billion/day in 2025) do not bother them. They focus on asking for even more budget every year despite the absence of a clear economic or social crisis, which, like the lockdown of 2020-2021, is the basis for increasing subsidies in the first place.

Finally, the pensions of military and uniformed personnel (MUP), which averaged about P110 billion/year by 2024, increased to P144 billion this year and are proposed to increase to P198 billion next year. This is a clear example of wasteful and outrageous spending that will punish taxpayers today and tomorrow. Congress and the President must rein in that spending. Even better, if active MUP officials were more sensitive to taxpayers and accepted the public finance burden of the scheme, they themselves might someday voluntarily contribute to their pensions. And stop the injustice of pension indexation with the salaries of active MUPs.

Bienvenido S. Opalas, Jr. Bienvenido S. Opalas, Jr. is president of Research Consultancy Services and Minimal Government Thinkers. He is an international fellow of the Tholos Foundation.

minimum government@gmail.com