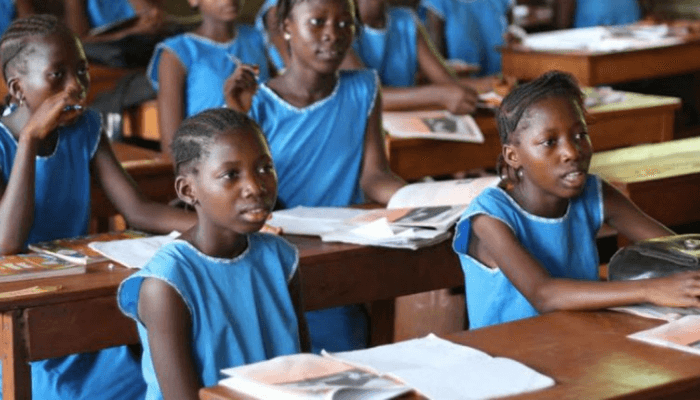

Laws designed to protect women and girls exist in name throughout Nigeria, but their impact is not felt. While some states have taken steps to domesticate the Violence Against Persons Act (VAPP) and the Child Rights Act, many states are still struggling to implement them in a way that keeps girls safe, protected, and in school. The result is a growing gap between policy and actual reality, especially for the poorest families.

This is according to the new state-by-state assessment of Women Economic Empowerment (WEE) released by BudgIT on Wednesday.

“Child protection, development and family cohesion are not just policy objectives. They are national imperatives,” said Women's Affairs Minister Hajiya Iman Sulaiman Ibrahim.

His warning reflects what is happening across the country as states are passing laws without the systems needed to enforce them.

Also read: We are taking steps for the safety of every girl in Bauchi – Mohammed

Budgit reports that in the south, Cross River offers a rare example of what enforcement can look like when supported by political will. The state is known for its investment in women's participation in the economy and digital skills.

Its 2024 budget allocated over N800 million for digital literacy programs for women, including an ICT forum for women and children as well as training for 100 girls in graphic design, web design and web hosting. Although the state has no women-specific funding in the creative or cultural sectors, its approach to technology and literacy shows a focused commitment to emerging industries.

More importantly, Cross River is the first state to introduce a Multi-Sectoral Costed Action Plan (CAP) to implement the VAPP law. The plan, designed to run from 2023 to 2027, outlines clear activities, responsible actors and budget allocations to combat sexual and gender-based violence. It provides a funded, practical structure for implementing the VAPP legislation. With female enrollment in primary school at 85.9 percent and only 6.5 percent out of school, the state shows how legal protection and education efforts reinforce each other.

The report's findings show that this is in stark contrast to conditions in states like Sokoto, where female education indicators are among the lowest in the country. According to MICS 2021 data, female literacy is just 16.4 percent, only 3.5 percent of women complete higher education, and 66.4 percent of girls who are poor are out of school. The state has the lowest secondary school attendance for girls in Nigeria, with a combined 15.8 per cent attendance at the junior and senior level.

Out of 42,862 teachers, only 11,098 are women. Although Sokoto has domesticated both the VAPP Act and the Child Rights Act, shortcomings in enforcement and implementation are increasing the incidence of insecurity, early marriage and school dropout.

Interferences are present. With support from development partners, the state has brought more than 418,000 school girls into classrooms through cash transfers, school meals, girl-to-girl mentoring and female teacher training. Projects such as Save the Child Initiative's outreach program in Sokoto also provide psychosocial support, mentoring and vocational training to help adolescent girls return to school or acquire income-earning skills. But without strong enforcement of protective laws, progress remains fragile.

Also read: Protecting women and educating girls accelerates peace in Nigeria's crises

According to the report, Yobe also faces similar challenges. With only 41.4 percent girls enrolled in primary school and 21 percent girls in senior secondary, the state's out-of-school rate stands at an alarming 59.3 percent. Female literacy is 22.2 percent and the rate of women completing higher education is only 5.6 percent.

Poverty, insecurity and cultural norms remain major barriers, which are worsened by weak implementation of the Child Rights Act and the VAPP Act. Yobe has launched several programs, including the World Bank-supported AGILE project, which is building 50 new girls' secondary schools and rehabilitating 225 others, and providing vocational and digital skills training.

These statistics reveal much more than economic hardship. They point to systemic failures in legal protections. In states where implementation is weak, early marriage and gender-based violence are on the rise, prompting families to withdraw girls from school for perceived safety. Many states still lack sexual assault referral centres. Some domesticated laws but did not make the consequential amendments necessary to implement them.

In states like Benue, where both the VAPP Act and the Child Rights Act are in force, shortcomings remain in tackling the social barriers that keep girls out of classes. Experts recommend targeted public awareness campaigns and strong community involvement to challenge norms that discourage girls' education.

The Minister of Women Affairs has warned that violence against minors is increasing rapidly in Nigeria. “Every day, we get about 10 cases of gender-based violence and eight of those 10 are minors,” she said. They also highlighted the growing threat of digital harm, including extortion, bullying, sextortion and grooming. “Our VAPP Act is 10 years old. The reforms will include safeguards on digital dimensions,” he said.

The federal government is reviewing the Child Rights Act and also updating the National Child Policy to ensure complete domestication. It is also creating a child protection research and information center as well as a national child protection database and child welfare index, supported by UNICEF.

But the strongest legal framework cannot succeed without enforcement at the state level. The Cross River model, with its costed and funded action plan, shows the way forward. Nigeria's progress depends not on passing new laws, but on the courage of governors to fund, implement and enforce what already exists.