For more than five years, the Southeast lived in the shadow of Monday's fateful ritual. What began as a political protest turned into a tool of economic strangulation, fear, and criminal enterprise. Now, as Anambra State Governor, Charles Soludo, has announced that the region has lost more than 20 percent of its economy annually during the crisis, the moment demands more than celebration, but also serious reflection.

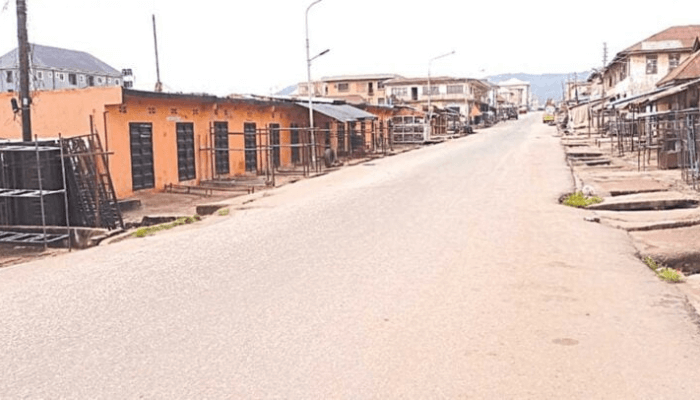

Twenty percent annual economic loss is not a figure that can be hidden. This means closed shops in Onitsha, deserted markets in Aba, silent classrooms in Owerri and halted factories in Nnewi. This means lost jobs, lower incomes, declining tax revenues and deeper poverty. For a region already struggling with infrastructure shortage and capital flight, the cumulative impact of five years of stagnation is staggering.

The tragedy of the stay-at-home order was not just economic; It was political and deeply institutional.

Also read: Sit at home: South-east lost 20% annually as criminals held the region hostage for five years – Soludo

The stay-at-home directive was rooted in long-standing grievances – perceived marginalization, distrust of federal authority and agitation over the detention of Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) leader Nnamdi Kanu. In its early stages, many residents complied out of sympathy or solidarity. But what started as civil disobedience gradually turned into coercion.

Enforcement slipped out of the hands of agitators and into the hands of armed gangs who weaponized fear as open businesses were attacked, vehicles burned and civilians attacked, blurring the line between political protest and organized criminality. And this is where the failure of leadership became clear.

The five governors of the southeast rarely spoke with one voice. There was no consistent, coordinated regional strategy; Instead, responses were fragmented. One state relaxed enforcement while another remained vigilant; One governor issued threats while another demanded negotiations; One relied heavily on security operations while the other was treading cautiously. The absence of a unified front encouraged criminals and confused citizens. The crisis demanding regional cohesion was treated as a problem of a separate state.

In federations, governors are the chief security officers of their states, but insecurity does not respect state borders. Criminal camps linked jungles across borders, while enforcers often operated lightly from one state to another. Without intelligence sharing, joint operations, and cohesive messaging, enforcement gaps widened. And it is this void that criminals eagerly fill.

“Criminal camps were linked by forests across borders, while enforcers often operated lightly, from one state to another. Without intelligence sharing, joint operations and cohesive messaging, the enforcement gap widened. And it is that void that criminals eagerly fill.”

It took several years for the camps to be seriously destroyed, such as 62 in Anambra that were reportedly decommissioned. That effort, while admirable, raises a difficult question: Why did it take so long for a coordinated security architecture to emerge?

Furthermore, beyond tight security, there was a lack of messaging. The region lacked a unified political communication strategy to convince citizens that sitting at home had become counterproductive. The silence or contradictory signals from leaders allowed fear to masquerade as consensus. This was a case where legitimate authority appeared to be uncertain, allowing illegitimate authority to flourish.

Security actions alone cannot guarantee that such a disruption will not happen again. The crisis of sitting at home is based on three underlying weaknesses.

First, political alienation, where many youth in the south-east feel alienated from national power structures. Perception, whether completely accurate or not, has emotional potential. Unless federal appointments, infrastructure projects, and economic policies clearly reflect inclusivity, the movement's stories will find fertile ground.

Second, economic fragility in a sector highly dependent on small and medium enterprises makes it particularly vulnerable to disruptions. Informal traders and daily wage earners cannot tolerate repeated shocks. Diversifying the regional economy, investing in industrial clusters and strengthening digital commerce can build resilience against future disruptions.

Third, youth unemployment and criminal opportunism, as idle hands, were easily recruited into enforcement agents. Tackling cultism, weapons proliferation and gang networks requires sustained social investment, skills training, apprenticeships, microcredit and rehabilitation programs – not just raids.

We believe that if house sitting enforcement is coming to an end, it should actually mark the beginning of structural reforms, such as:

Institutionalized regional cooperation: The South-East Governors Forum should evolve from a formal body into an operational security and economic council. Joint intelligence task forces, shared surveillance infrastructure and harmonized security laws are important. Regular joint briefings will also demonstrate unity and not give place to misinformation.

A political engagement strategy: 'Dialogue' does not mean surrender, meaning that governors, traditional rulers and civil society leaders should continue structured dialogue with non-violent agitators and community influencers. Where complaints are constitutional, they should be aired through legal advocacy. Where actions are criminal, they should be clearly distinguished and prosecuted.

Federal-regional partnership: President Bola Tinubu has emphasized national security as a priority. That commitment must translate into actionable cooperation (better financing for regional security initiatives, faster judicial processes for terrorism-related cases, and concrete economic investment in the south-east). Also, a visible federal presence in sectors such as infrastructure, industry and appointments will help counter narratives of neglect.

Also read: Insecurity: Northern leaders pledge support for peace in South-East, South-South

Recovery plan from the economic shock: After five years of economic disruption, the sector deserves a coordinated recovery package. Tax incentives for affected businesses, credit facilities for SMEs and investment summits showcasing improved security could help restore investor confidence. The Christmas surge in activity described by Soludo is encouraging, but the improvement must be institutional, not seasonal.

Civic education and reframing the narrative: The psychological grip of fear must be broken. Public campaigns emphasizing the costs of compliance in schools, hospitals, and markets may reinforce the understanding that mass self-harm only benefits criminals.

It is easy to blame criminal elements. It is difficult, but necessary, to accept that leadership hesitation and regional disunity prolonged the crisis. The Southeast has historically been entrepreneurial and resilient. It should not have been held hostage every Monday for half a decade.

The lesson is clear: insecurity thrives where coordination fails.

If governors maintain unity, invest in economic resilience, engage constructively with disagreements, and cooperate strongly with Abuja, the region can turn this painful chapter into a turning point.